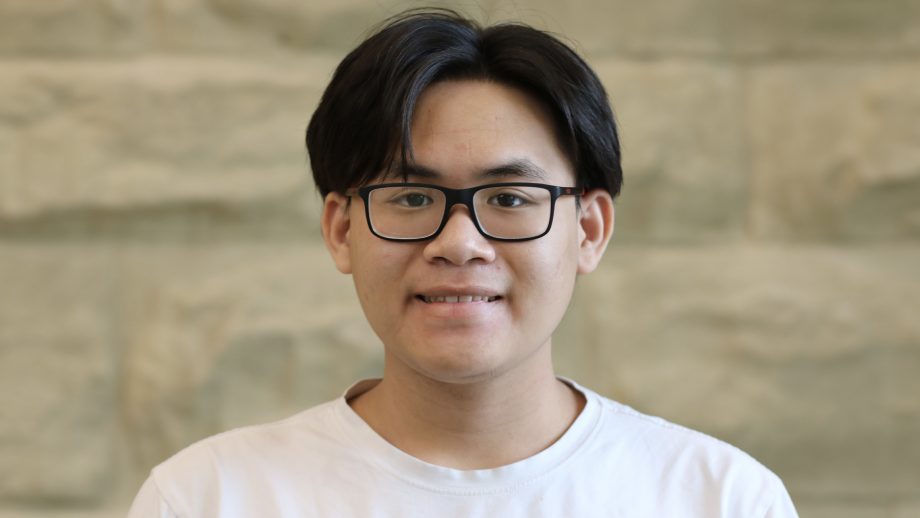

Dr. Christine Schreyer learns Kala from children in Papua New Guinea in 2017. Photo by: David Lacho

Like most superheroes, Dr. Christine Schreyer leads a double life.

By day, the St. Andrews native and UWinnipeg alumna has the unassuming role of researcher and associate professor of anthropology at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus.

But remove the proverbial glasses, and Schreyer’s second identity leaps into action — creator of fictional languages for some of the biggest Hollywood blockbusters of the last few years, including the Kryptonian language used in the 2013 film Man of Steel.

Schreyer’s work has taken her from the shores of Papua New Guinea to movie sets in Vancouver, all in service of revitalizing — or in some cases creating — language. As she explains it, there’s more in common with her dual worlds than first appears, and plenty to be learned from what binds them.

Origin story

An aspiring anthropologist from the age of 12, Schreyer developed an interest in Cree languages during her studies at UWinnipeg, thanks to classes she took with professors George Fulford (Algonquian ethnography) and Ida Bear (Cree language).

“I was interested in what’s called polysynthetic morphology — all the pieces of Cree and how long the words were — and it was so different than anything else I had studied,” says Schreyer.

Schreyer continued to pursue her passion following her graduation in 2001. Her PhD research at the University of Alberta provided one of her earliest glimpses into how the revitalization of endangered languages has deeper meaning for Indigenous identity and land. That work involved studying how two communities — the Loon River Cree First Nation in northern Alberta and the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in northern British Columbia — negotiated the terms of external mining, logging, or oil drilling within their districts.

“They would build in policies that would protect language within protecting the land and each community saw language as one resource of the land, which had grown in that environment.”

Creating alphabet

Schreyer’s first experience creating an alphabet came in 2010, shortly after she was hired as a tenure track assistant professor at UBC. A colleague offered her the opportunity to travel to Papua New Guinea, where an Indigenous community was seeking assistance in developing an alphabet for their language — Kala — so they could teach it in their schools.

“I was worried that it would be harder to do than it was, because I was concerned that everyone would have very vocal opinions. But everybody there was in was consensus, and they wanted this to go forward.”

The alphabet used English letters, but had fewer due to fewer sounds spoken in Kala. For sounds that differed from those used in English, Schreyer and her team modified the letter.

“They have what’s called nasal vowels (commonly heard in French articles such as “un” or “en”). They had to be able to mark that nasal sound, so they chose a tilde symbol (~) that looks like a wave. They did that because they’re ocean people and to them waves were very common and it made sense to have waves.”

A(vatar) to Z(od)

Soon after returning from Papua New Guinea, Schreyer started teaching a course on created languages. At the same time, the blockbuster movie Avatar had been gaining a massive following since its release one year earlier, particularly among fans who had taken to learning the fictional language of the Na’vi, inhabitants of the film’s extraterrestrial moon setting.

“Na’vi speakers” became the subject of classroom discussion, and piqued Schreyer’s interest enough that she decided to survey fans across the globe about their obsession. Results from 300 people and 47 countries showed the reasons went beyond simply enjoying the movie.

“A lot of them just loved language, and they loved the Na’vi language more than they loved the movie,” says Schreyer. “They also found it was a really judgment-free zone. Sometimes people have the concern, as settlers, if we’re learning an Indigenous language, are we appropriating that? … People felt because it was a made-up language, they didn’t have that anxiety.”

Eventually, media began to pick up Schreyer’s research. One story from the Globe and Mail caught the eye of Alex McDowell, the production designer on Man of Steel, who happened to be flying to Vancouver to prepare the set of Krypton, home planet of the film’s hero, Superman. The plan at that time was to decorate the set with nonsensical writing standing in for the Kryptonian language.

“He realized through reading the article they couldn’t make it gibberish because fans care about these kinds of things,” says Schreyer.

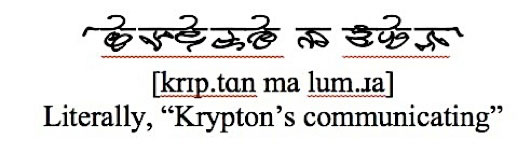

An example of Schreyer’s Kryptonian alphabet. Credit: Christine Schreyer

An email from McDowell’s assistant had Schreyer en route to Vancouver, where she was tasked with creating a Kryptonain language to be used on set, as well as in marketing materials. Working with the film’s art director and graphic designer, Schreyer was able to find influence from decades of Superman lore, using names like Kal-El (Superman’s Kryptonian name), Jor-El (Superman’s father), and Zod (the villain) to form a basis for her language.

“I was able to take those names and make a sound system, and then figure out patterns of sound, and how can we then make words out of those that matched how these words were developed. So that was my first step.”

Superman’s famous crest — the “S” meaning “hope” in Kryptonian — provided a starting point for the alphabet’s design, while an existing number system that flipped depending on a given character’s meaning drew comparisons to a familiar language for Schreyer.

“When they told me [about the number system], the first thing that came to mind were Cree syllabics, because Cree syllabics flip depending on which vowel it is, so that will shift the shape. So the Kryptonian writing system is actually based on Cree syllabics, which I learned at The University of Winnipeg.”

Following her work on Man of Steel, Schreyer was approached to create an alien language for the 2017 film Power Rangers, which included the first instances of one of Schreyer’s fictional languages being spoken on-screen.

WATCH: Dr. Christine Schreyer explains the process behind her Kryptonian. Credit: UBC Okanagan

Lessons from the Na’vi

Learning fictional languages may be a fun way to immerse yourself in fandom, but according to Schreyer, there are real lessons to be taken away from the practice. She offers Avatar fans as an example, noting how their immersion in the film’s language led them to further explore the movie’s themes of environmentalism and activism against colonization.

“I feel like the people that I surveyed, they were interested in environmental ethics, so it was the killing of the beautiful world people were concerned with,” says Schreyer. “A lot of people do relate it back to Indigenous cultures and the tar sands, or whatever else is happening around the world. I think it leads them to more of an interest in Indigenous cultures.”

Cultural stories can be found in everything from Canada’s many dialects of Cree to the fantastical languages of fiction (the sentence structure of Schreyer’s Kryptonian, for instance, reflects a selfish society that obsesses over its objects). It’s one of the reasons the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has identified preserving Indigenous languages as one of its calls to action. Teaching those endangered languages, Schreyer says, is an important step towards reconciliation.

“I think a lot of the work of reconciliation is for non-Indigenous people to learn about the people who were here before, and you cannot have a language course without having that cultural piece embedded within it.”

Adam Campbell

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2018 edition of UWinnipeg Magazine.